Following

the Trickster

Copyright © 2010

by Richard S. Platz, All

rights reserved

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Fox Creek, Virginia, and Section Line Lakes Backpack

Trinity Alps Wilderness

Klamath National Forest

August 21-24, 2009

Photos by the

Author and Barbara Lane Except Where Noted

"We would carry him along in our hearts"

Our friend Mr. Popper, master of practical jokes,

had died the previous Fall. On the final day of September he

succumbed to a glioblastoma. Nancy had been at his side. He

never intended to leave her alone – his love, his companion,

his soul mate and friend – but what could he do? Ol' Death

had come unbidden that night and whisked the Trickster away.

Rudely summoned from her lullaby of lifelong

harmony, Nancy awoke to a nightmare of bereavement. She dealt

with it the best she could. Ten months of tattered days had

fluttered past by the time we invited her to join us on a four-day

backpack into Fox Creek Lake. Popper and Nancy and Barbara and

I had backpacked several times together, most recently in August

2006 to Patterson Lake in the South Warner Wilderness (see Highway 299 Revisited

). That

was Popper's last backpack. Now, being dead, he could of course

no longer shoulder a backpack. So instead we agreed to carry

him along in our hearts.

Fox

Creek Lake is one in a cluster of four lakes situated in a high

rocky canyon at the head of the Fox Creek drainage on the northernmost

slopes of the Trinity Alps Wilderness. Glaciers had ground out

cirques from the Mesozoic granite bedrock of the Craggy Peak

Pluton, spilling the tailings northward as an apron of moraine.

Fox Creek cuts northward from the lakes through the glacial

till to join the South Fork of the Scott River, thence the flow

continues north to irrigate alfalfa fields of the Scott Valley.

Of the four, only Fox Creek Lake and Mavis Lake can be accessed

by a maintained trail.

Fox

Creek Lake is one in a cluster of four lakes situated in a high

rocky canyon at the head of the Fox Creek drainage on the northernmost

slopes of the Trinity Alps Wilderness. Glaciers had ground out

cirques from the Mesozoic granite bedrock of the Craggy Peak

Pluton, spilling the tailings northward as an apron of moraine.

Fox Creek cuts northward from the lakes through the glacial

till to join the South Fork of the Scott River, thence the flow

continues north to irrigate alfalfa fields of the Scott Valley.

Of the four, only Fox Creek Lake and Mavis Lake can be accessed

by a maintained trail.

I had been to Fox Creek Lake before with the

Annual Spring Acid Backpack Group. That was in July of 1984.

A quarter of a century had passed, and my recollections were

faded and threadbare, though some few swatches of whole cloth

remained.

On one such scrap I found embroidered memory

of the steep hike up to the lake. James Aaron and Joan had joined

me from Chico. As we sweated uphill in the blazing sun, I recall

observing, "Every backpack is painful. It's just

that the pain lasts longer on some than on others."

I recall it all because that same thought has returned like

a homeless pigeon during subsequent hikes of every season.

Mr. Popper played a memorable role on that earlier

trip. He had led the group on a dayhike from Fox Creek Lake,

where I believe we were camped, over the ridge to Virginia Lake,

thence cross-country up to the Pacific Crest Trail on the high

granite cliff above Section Line Lake. I recalled nothing of

Fox Creek or Virginia Lakes, not the forest, not our campsite,

not the terrain. But seared into my memory was that act of pure

madness when, following Popper, we had scrambled down a vertical,

rocky couloir on an ill-advised and dangerous shortcut from

the PCT straight down to the south shore of Section Line Lake.

Everyone on the dayhike had followed along. Not one had turned

back. Peer pressure ruled, I guess, and youthful delusions of

indestructibility. Miraculously, no one had broken a single

bone. Clearly I recall the plunge of sweet relief into the icy

waters of the lake and then sunning ourselves naked on the rocks.

Neither Nancy nor Barbara had been to Fox Creek

Lake. Though we included it annually on our list of possible

backpacks, it was a chance conversation at a birthday party

a few weeks earlier that had determined our fate. Barbara had

chatted at length with a new acquaintance, an avid backpacker,

who advertised Fox Creek Lake as one of her favorites.

I could not recall the lake at all. The map gave

the trail distance as four miles and the climb 1,300 feet. Not

insignificant, but hopefully still within our range. The suicidal

scramble down to Section Line Lake from the PCT could easily

be avoided by a leisurely three-quarter-mile stroll up-slope

from Fox Creek Lake. Or so it seemed in the planning.

This backpack would be Nancy's first since Popper

passed away. She chose to bring along her longtime friend and

neighbor Patricia. This was fitting, since both were younger

than Barbara and I and thus more attuned to a rhythm of vigor

and impulse. We, in our dotage, were more set in our ways.

Access to the Fox Creek trailhead is from the

dying little town of Callahan in a southeast twitch of the Scott

Valley tail. Nancy and Patricia would drive in Nancy's station

wagon and meet us at the rustic, drive-in campground at Scott

Mountain Summit. There, at 5000 feet, we hoped to find the night

air cool enough to sleep. Next morning we would drop down to

Callahan, drive the short distance to the trailhead, and get

an early start hiking.

Barbara and I departed Blue Lake in the early

afternoon on Thursday. The river valleys were mercilessly hot.

At the Straw Bale House in Big Bar the temperature stood at

101. In Weaverville, where we bought sandwiches and gas, the

thermometer soared to an inhuman 105. Fortunately our van was

endowed with air-conditioning, but we fretted that Nancy's station

wagon was not.

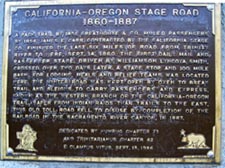

A

weathered plaque commemorates the historical significance of

the Scott Mountain Summit, proclaiming something about toll

roads and Indian raids. We arrived there before five o'clock

and found a large, shady campsite halfway back to the meadow,

where we ate our sandwiches in the lingering heat. Mr. Popper,

Barbara, and I had camped together in this same campsite in

1994 on our way to Grizzly Lake (see Shortcut

Into Grizzly Lake ). Only one other person was settled

within the campground proper, a long-haired fellow and his dog

in the next campsite, across the road from the only pit toilet.

A

weathered plaque commemorates the historical significance of

the Scott Mountain Summit, proclaiming something about toll

roads and Indian raids. We arrived there before five o'clock

and found a large, shady campsite halfway back to the meadow,

where we ate our sandwiches in the lingering heat. Mr. Popper,

Barbara, and I had camped together in this same campsite in

1994 on our way to Grizzly Lake (see Shortcut

Into Grizzly Lake ). Only one other person was settled

within the campground proper, a long-haired fellow and his dog

in the next campsite, across the road from the only pit toilet.

The gentle knoll above was blighted by a small

city of recreational vehicles, travel trailers, people, dogs,

and yelping children in a camping area we had never seen, apparently

a rogue arm of the campground separating us from the PCT. It

looked like they were planning a lengthy stay. A converted school

bus had "CHRISTIAN OUTDOOR GARDEN OF CHILDREN," or

some such, painted on the side. I felt a little uneasy, like

camping next to the Branch Davidian compound in Waco.

"All relatives," explained a young

man emerging from the toilet. "Just a family get-together."

Mollified, we settled in, hiked down to the Darlingtonia

fen, then took the PCT south a little ways toward the Marshy

Lakes. Back at camp we built a small fire with split logs we

had brought from home. As it grew dark, we watched the stars

emerge against a blackening sky.

Around nine o'clock or so, with the fire reduced

to glowing coals, blinding headlights and a bug-spattered grill

poked a roaring snout into camp. Nancy and Patricia climbed

out of Nancy's station wagon. They had gotten a late start.

Without air conditioning, they had stopped to swim in the North

Fork of the Trinity River, then dawdled over dinner at the Bear's

Breath at the Trinity Alps Resort. They had spent half an hour

searching for us through the campground in the dark. By headlights

and flashlights they spread out sleeping bags on the broad flat

campsite. No tents. We all turned in by ten o'clock.

Friday was forecast to be another blistering

day, so we arose with the first hint of dawn to get an early

start hiking in. I wanted to leave by eight o'clock, drive to

the trailhead, and start our hike by nine. But things did not

work out that way.

Barbara and I ate breakfast, packed our backpacks,

stowed the van, and were ready to go by a little after eight.

Nancy and Patricia were still chatting and packing up. We lent

them a 2-way radio and started down the highway toward Callahan,

where we would meet.

No more than five miles down the highway, at

the cusp of broadcast range, we heard a garbled message on the

radio. Something about car trouble. We turned around and found

our friends on the side of the road just below the Scott Mountain

crest. The right front tire was flat as a pizza. Nancy had a

spare, but it was soft. Fortunately we had a 12-volt air pump,

so we pumped up the spare and bolted it on. The process ate

into our precious morning cool.

At Callahan, we studied the map, asked a passing

tourist who knew nothing, then took South Fork Road which shortly

intersected with desired Forest Road 40N17. We puzzled our way

through a couple of intersections without benefit of signs,

climbed southwest until we passed the East Boulder trailhead,

and finally arrived at the signed Fox Ridge Trailhead about

ten (N 41 14' 58.13", W 122 50'

03.22", 5388 feet). The parking lot offered plenty of space,

was flat, graveled, and groomed, and sported only two other

cars. When we began our hike a little later, the air temperature

was still bearable. In the shade.

The

trail ascended steeply south in blazing sun through tall manzanita,

up a long, straight medial moraine that divided the Fox Creek

canyon to our right (west) from the West Boulder Lake drainage

to our left (east). The Fox Ridge. After a quarter mile we crossed

another graded road and entered the wilderness. As the trail

rose southward, the sparse Ponderosa pine gave way to an ever-thickening

mixed-conifer forest of white and red fir, white pine, a few

scattered incense cedars, and at least one Brewer's spruce.

The

trail ascended steeply south in blazing sun through tall manzanita,

up a long, straight medial moraine that divided the Fox Creek

canyon to our right (west) from the West Boulder Lake drainage

to our left (east). The Fox Ridge. After a quarter mile we crossed

another graded road and entered the wilderness. As the trail

rose southward, the sparse Ponderosa pine gave way to an ever-thickening

mixed-conifer forest of white and red fir, white pine, a few

scattered incense cedars, and at least one Brewer's spruce.

Nancy and Patricia would hike on ahead, then

wait for Barbara and me to catch up. This suited me, for I found

that their constant dialogue, enjoyed by many hikers, would

distract me from the silent communion with nature and each other

that Barbara and I customarily enjoyed.

After an hour of hiking, our medial moraine merged

with the terminal moraine that clothed the steep north slope

of the main mountain block.  At

an open meadow, steeply tilting above a grassy swale, Nancy

and Patricia had stopped to rest. Perched on rounded granite

boulders exposed from the moraine, we ate trail bars or handfuls

of gorp and enjoyed the view north into the Scott Valley. Already

we had climbed high above Fox Creek and could see the valley

floor below us arcing southwestward, rising toward a distant

ring of jagged pinnacles and granite cliffs, which seemed to

have migrated too far north. Our orientation

had grown askew as the trail slowly wheeled, undulating in and

out of gullies and ravines. We would continue to climb, following

the greater arc of the higher mountain slope in a broad clockwise

loop until, like a horseshoe, the trail would intercept the

creek as it spilled from Fox Creek Lake.

At

an open meadow, steeply tilting above a grassy swale, Nancy

and Patricia had stopped to rest. Perched on rounded granite

boulders exposed from the moraine, we ate trail bars or handfuls

of gorp and enjoyed the view north into the Scott Valley. Already

we had climbed high above Fox Creek and could see the valley

floor below us arcing southwestward, rising toward a distant

ring of jagged pinnacles and granite cliffs, which seemed to

have migrated too far north. Our orientation

had grown askew as the trail slowly wheeled, undulating in and

out of gullies and ravines. We would continue to climb, following

the greater arc of the higher mountain slope in a broad clockwise

loop until, like a horseshoe, the trail would intercept the

creek as it spilled from Fox Creek Lake.

When

we resumed our hike, the trail ascended through a tilting, healthy,

northwest-facing forest underlain with glacial till, until it

gradually hooked westward, and we began to climb a series of

lovely moraine terraces. Tall red firs decorated little alpine

gardens of low manzanita and wildflowers, and brilliant white

granite rocks and boulders studded the loose duff. As we climbed,

the forest grew more open, allowing the sun to broil us as we

trudged between the shrinking islands of shade. In time the

trail crested a divide and began to drop through an open graveyard

of exhumed boulders to a dry stream bed. There we came at last

to a trail junction and a sign. One arrow pointed steeply uphill

toward the Pacific Crest Trail, several hundred feet above.

I unfolded the map. The route was called the Wolford Cabin Trail.

Beyond the crest it dropped south to Wolford Cabin and a junction

with the Granite Creek Trail in the Coffee Creek drainage.

When

we resumed our hike, the trail ascended through a tilting, healthy,

northwest-facing forest underlain with glacial till, until it

gradually hooked westward, and we began to climb a series of

lovely moraine terraces. Tall red firs decorated little alpine

gardens of low manzanita and wildflowers, and brilliant white

granite rocks and boulders studded the loose duff. As we climbed,

the forest grew more open, allowing the sun to broil us as we

trudged between the shrinking islands of shade. In time the

trail crested a divide and began to drop through an open graveyard

of exhumed boulders to a dry stream bed. There we came at last

to a trail junction and a sign. One arrow pointed steeply uphill

toward the Pacific Crest Trail, several hundred feet above.

I unfolded the map. The route was called the Wolford Cabin Trail.

Beyond the crest it dropped south to Wolford Cabin and a junction

with the Granite Creek Trail in the Coffee Creek drainage.

A few steps up the trail a second sign announced

that Mavis Lake was nigh, though not exactly where. Nancy and

Patricia conferred. "Do you want to go on up and take a

look at Mavis?" Nancy asked us. "Wherever it may be."

The hiking books had described Mavis as not very

attractive. Art Bernstein called it "shallow, mucky,"

and "not worth the long walk." The map showed the

Fox Ridge Trail continuing westward, at one point passing just

a couple hundred feet below the north end of Mavis, then on

around a ridge another mile to Fox Creek Lake. I looked at Barbara.

We were already tired and overdue for lunch. I gestured on up

the main trail, and Barbara nodded.

"I think we're gonna keep on going to Fox

Creek Lake," I replied. "Maybe we'll catch it on the

way out."

Nancy and Patricia discussed their options. Then

Nancy announced, "Patricia and I are going to go look for

Mavis."

"That's fine," I said.

"We'll see you at Fox Creek in a little

while," Barbara added.

Our companions left us, and a little further

along the trail we stopped for lunch. The last leg of the journey

climbed around an open, rocky ridge of bedrock and granite blocks,

dropped into the forested Fox Creek Valley, then climbed again

in one last scramble to the lake. Though only a mile, the hike

was tiring.

Barbara

and I arrived at Fox Creek Lake a little after two. The trail

dead ended at a primo site on the north shore of the lake (N

41 12' 41.2", W 122 50' 57.3", 6552 feet). The camp

was vacant, so we leaned our backpacks against the wall of a

massive, flat-toped boulder, big as a cabin, overlooking the

water. The ground was open, clear, flat, and spacious, with

a substantial fire ring, logs to sit on, a flat slab propped

up for a table, and easy access to the lake. The sturdy forest

of red fir, mountain hemlock, and lodgepole and white pine provided

plenty of shade and hammock sites. A narrow buffer of trees

and brush separated us from the lake.

Barbara

and I arrived at Fox Creek Lake a little after two. The trail

dead ended at a primo site on the north shore of the lake (N

41 12' 41.2", W 122 50' 57.3", 6552 feet). The camp

was vacant, so we leaned our backpacks against the wall of a

massive, flat-toped boulder, big as a cabin, overlooking the

water. The ground was open, clear, flat, and spacious, with

a substantial fire ring, logs to sit on, a flat slab propped

up for a table, and easy access to the lake. The sturdy forest

of red fir, mountain hemlock, and lodgepole and white pine provided

plenty of shade and hammock sites. A narrow buffer of trees

and brush separated us from the lake.

Our water bottles were empty, so Barbara unstrapped

the gallon plastic jug while I pulled out the water filter and

pump. We waited to deploy the rest of our equipment until our

companions arrived and bestowed site approval. That gave me

the chance, as was my habit, to explore the vicinity for alternative

campsites before commitment.

The campsite was perched on

the domed lip of the bedrock bowl that held the lake, and was

paved with exposed boulders, glacial till, and forest duff.

We found an easy path down to the water's edge and stood on

the long north shore looking south across the lake. The water

had dropped two feet from its high mark of earlier in the season,

leaving the shore wide and grassy, an easy corridor around the

lake. The ridge to our left (east), around which we had horseshoed

in from Mavis Lake, was low, but ascended southward to a high,

distant crest. Beneath the ridge the water was shallow, with

broad patches of lilypads wavering offshore from green swathes

of grassy meadow.

Palpably missing across the lake was a sheer

granite headwall. Instead, a rising bowl of dense forest stretched

up and away for half a mile, obscuring the white granite rock

and talus from which it grew. Above and behind this imperfect

forest curtain, patches of talus, rock cliff, and ridge crest

spires peeked through. To the southwest loomed a high crenelated

dome of exposed granite, the highest point, from which a bare

leg of slickrock granite descended to plunge beneath the deep

water and dam the west end of the lake. The map showed it to

be a ridge that divided Fox Creek Lake from the canyon beyond,

which harbored Virginia Lake. We heard voices coming from that

direction. We were, alas, not alone.

After sculpting this lake basin, the glaciers,

as they withdrew to a higher, colder clime, had carved the upper

canyon, rock by rock and grain by grain, in a series of bedrock

cirques and terraces, then partially refilled them with stones

and till released from the melting ice and blocks of granite

split off from the towering cliffs above and sledded down the

snow. In the distance to the southeast was our longest view,

a valley that offered a glimpse of a sheer cliff, which probably

stood as the headwall above Section Line Lake. The ridge above

it provided a fairly level base on which the Pacific Crest Trail

could traverse east and west.

Mr. Popper stood here once, beheld this vista.

I wondered what became of all his memories. They had begun to

fade like photos left out to bleach in the sun before the album

was finally closed. As had my own. Was that not why I scribbled

down these frail accounts?

Barbara volunteered to dip water from the lake

and pump it into drinking bottles while she waited for Nancy

and Patricia at the campsite. In quest of a more perfect campsite,

I strolled along the shore toward the granite ridge rising over

the west end of the lake. Two men were standing on a huge, rounded

boulder that plunged into deep water. They were neatly dressed,

perhaps in their twenties, and engaged in a loud banter as if

strutting on the frat house steps for all to see. As I approached,

I discovered a third man leaned against the rocks and actually

typing something into his laptop. Their bright polo shirts and

neatly creased golf shorts seemed out of place in the wilderness.

Overlooking the lake, yet oblivious to it, they seemed bent

on bludgeoning into submission everything wild and sublime with

cleverness, their dandy clothes, and digital toys. They made

a point of ignoring me.

I passed a little patch of water lilies floating

in the shallows, then, just before the trail entered a grove

of alders at the northwest corner, I sang out cordially, "Hello.

You fellows come in on the Fox Ridge Trail?"

The nearest deigned to twist his head. "No.

Came in the other way." He waved vaguely over the

distant mountain as he turned his back on me. Dismissed. Conversation

ended.

So I followed the trail through the alders and

climbed up the slickrock saddle behind them searching for campsites

beyond. Their tents and backpacks were crowded into a small

clearing behind the rocks, and I veered around it as much as

the terrain would allow. Beyond them I continue a short distance

along the west shore trail and found a couple of small, rough

campsites, but it soon became apparent we had already taken

the best.

Back at camp I related my close encounter to

Barbara as we pitched our tent in a flat clearing well away

from the substantial rock fire ring. We had learned long ago,

when camping with others, not to set up too near the campfire

lest fireside prattle keep our slumber at bay.

Nancy and Patricia arrived a short time later.

Pleased with our choice of campsites, they propped their packs

against the big rock.

"How was Mavis?" Barbara asked.

"Small and shallow," Nancy replied.

"But it didn't dissuade Patricia from taking a dip."

"There was a nice sandy beach," Patricia

explained.

We all walked down to the

lake. The water was a perfect temperature for a swim, so we

strolled west along the shore in search of a good spot. The

young frat boys had retired to their campsite, but when they

saw three females had arrived, they clambered out onto the rocks

again, pretending to fish. The gawking made the women uncomfortable,

so they retreated eastward along the shore. Patricia had brought

a swim suit, and Barbara and Nancy swam in their undies. Fearless,

I swam naked as usual.

By

the time we had finished deploying our gear, cocktail hour had

arrived. Cocktail time comes early in the wilderness. Something

about warding off bears or evil spirits, I believe. Nancy, draped

in a stunning blue sarong, offered tequila around, and I our

trademark amaretto. After numerous nips and sips and slugs,

we found ourselves jabbering and laughing in hammocks strung

around the campfire ring. Life was good. The camp felt like

home. Patricia had carried in a pint of Captain Morgan's Spiced

Rum, but before we got into that bad boy, the conversation turned

to dinner.

By

the time we had finished deploying our gear, cocktail hour had

arrived. Cocktail time comes early in the wilderness. Something

about warding off bears or evil spirits, I believe. Nancy, draped

in a stunning blue sarong, offered tequila around, and I our

trademark amaretto. After numerous nips and sips and slugs,

we found ourselves jabbering and laughing in hammocks strung

around the campfire ring. Life was good. The camp felt like

home. Patricia had carried in a pint of Captain Morgan's Spiced

Rum, but before we got into that bad boy, the conversation turned

to dinner.

I built a fire and Barbara quickly hydrated and

heated freeze-dried Three Cheese Lasagna, which sobered us.

Quick, tasty, and satisfying. Ingredients were probably listed

on the package. I never looked. When we returned from washing

our bowls and pot, Nancy and Patricia were concocting their

supper from scratch. With running commentary, they mixed, sampled,

boiled, and fried an array of rices, grains, veggies, roots,

and tubers, some with unpronounceable foreign names, for their

multi-course repast. It was like watching the cooking channel.

Patricia and Nancy had both brought tents, but

chose not to deploy them that night. Patricia spread her sleeping

bag out on a plastic ground cloth beside the big rock. Nancy

set hers up on top. We cautioned her about sleepwalking in the

dark, which might result in a ten-foot plunge, but she was not

too worried. The stars overhead made the risk worthwhile. As

darkness enveloped, we crawled into our tent.

Saturday morning Barbara and I arose with first

light, as was our custom, built a small fire to boil water,

and prepared our mocha and tea as silently as possible, so as

not to waken our comrades. Then we meditated for the better

part of an hour on our pads by the water's edge. When we returned

to camp for breakfast, our friends were just getting up and

beginning to fill the morning with the cheerful domestic banter

of an ordinary kitchen. Barbara joined in. Why, I wondered,

do folks so love to prattle on about food? Free range food.

Wild food. Nutritious food. Pernicious food. Ethnic food. Domestic

food. Exotic food. Erotic food. Flavor. Texture. Recipes. Cooking.

Buying. And always the restaurants with interesting menus.

Excusing myself, I retired to the lake shore

to commune with the voices of nature. The murmur of conversation

and laughter wafted down pleasantly from camp, a sound as natural

as the buzzing of cicadas. And as long as I could not make

out the words, those pesky little pirates could no longer

hijack my attention.

After breakfast Nancy and Patricia announced

that they had decided to backpack up to Virginia Lake and stay

overnight. We offered to dayhike along with them. Using the

GPS and dead-reckoning, we crossed the slickrock saddle above

the frat boys camp until it dropped into a thick forest on the

other side, where we found and followed sporadic cairns and

a few faint tracks. There was no trail. Our path looped back

southward and climbed through the woods at the margin between

the exposed granite blocks and talus above and the impenetrable

willows, alders, and brush that choked the valley floor below.

The pitch was steep and grew steeper.

Unable to follow the brush-choked outlet stream

from Virginia Lake, we instead were forced to scramble ever

higher into the sharp-edged granite blocks until we finally

crested a slickrock ridge to gaze down at Virginia Lake far

below us. For me the climb was deja vu. I had harbored a vivid

memory of this same approach, but could never have recalled

where or when it had taken place.

Barbara

and I were glad not to be toting backpacks as we all scrambled

down the talus slope to the water's edge. We arrived near a

picturesque little island at the outlet. Virginia was smaller

and cozier than Fox Creek Lake. More secluded. More remote.

The towering headwall of bedrock granite, being nearer, seemed

more sheer. Below the headwall, thick forest encircled the lake,

climbing from the grassy shore into the rough granite blocks

and talus split off from above. A wild place it was.

Barbara

and I were glad not to be toting backpacks as we all scrambled

down the talus slope to the water's edge. We arrived near a

picturesque little island at the outlet. Virginia was smaller

and cozier than Fox Creek Lake. More secluded. More remote.

The towering headwall of bedrock granite, being nearer, seemed

more sheer. Below the headwall, thick forest encircled the lake,

climbing from the grassy shore into the rough granite blocks

and talus split off from above. A wild place it was.

Nancy and Patricia found a perfect campsite right

beside the water (N 41 12' 20.4", W 122 51' 26.7",

6840 feet). No one else was there. The shore was brushy and

the lake's edge shallow, providing no easy access to the water,

except for a massive fallen log that entered the lake like a

dock. Nancy and Patricia swam off the log. The water, they claimed,

was cooler than Fox Creek Lake.

As

we picked at our lunch beside the fire ring, two women climbed

down the talus slope to join us. They wore khaki shirts with

Forest Service patches. The leader appeared to be in her forties.

Her companion was much younger, perhaps twenty, still in college

and learning the rangerette trade as a summer intern. They had

come around to check the campsites and clean out the fire pits.

We chatted as they dug out the ashes and dispersed them in the

surrounding bushes. We had plenty of questions for them, like

identifying trees and brush, and the best cross-country routes

to the PCT and Section Line Lake. They were agreeable and, in

the spirit of the Big Ranger, happily answered as best they

could, even though they were on a tight schedule and had to

make it back to their truck by nightfall. Then we watched them

circle the small lake, stopping to clean out fire pits and pack

out trash from two or three campsites we had not suspected were

there.

As

we picked at our lunch beside the fire ring, two women climbed

down the talus slope to join us. They wore khaki shirts with

Forest Service patches. The leader appeared to be in her forties.

Her companion was much younger, perhaps twenty, still in college

and learning the rangerette trade as a summer intern. They had

come around to check the campsites and clean out the fire pits.

We chatted as they dug out the ashes and dispersed them in the

surrounding bushes. We had plenty of questions for them, like

identifying trees and brush, and the best cross-country routes

to the PCT and Section Line Lake. They were agreeable and, in

the spirit of the Big Ranger, happily answered as best they

could, even though they were on a tight schedule and had to

make it back to their truck by nightfall. Then we watched them

circle the small lake, stopping to clean out fire pits and pack

out trash from two or three campsites we had not suspected were

there.

In mid-afternoon Barbara and I found our way

back to our camp at Fox Creek Lake. Having done it once, backtracking

the route was not as difficult. The frat boys had quieted down,

perhaps hungover. We went for a lazy swim, then laid on our

mats in the sun by the water. A man and boy, probably father

and son, wandered silently along the opposite shore, fishing.

We could not tell if they were dayhiking or backpacking. Later

we saw smoke from their campfire behind a stand of tall red

fir beyond the meadow at the southeast corner of the lake. Quiet

as shadows, they did not bother us.

The afternoon daydreamed past in a flash of silver,

and we were unable to tell if it was fish or water. A handsome

osprey fished the lake for our amusement. We saw water ouzels,

cormorants, flickers, chickadees, juncos, redbreasted nuthatches,

and hummingbirds. Though we enjoyed our tribe of four, the best

of all worlds allowed us to have a single night to ourselves.

The wind came up that night, rushing through

the branches with the roar of white-capped breakers. Gusts flapped

the walls of our tent. But inside we slept warm and snug.

Sunday morning was still breezy and colder. We

found harbor in the lee of the big rock, where we drank our

tea and mocha bundled in down jackets, enjoying the soughing

of the wind. From our new perspective, we determined that the

stout tree leaning over our tent was in fact dead and rotting.

Luckily the gusts had not blown it over and squashed us like

bugs. How, after all life's fuss, would that look on

the obituary page? The wilderness is not your Forest Service

campground, where hard-hat workers behind bands of yellow tape

prune away hazard trees and branches. Here, on your own, you

have to pay attention. So after breakfast, we dragged our tent

away from the snag.

Nancy and Patricia returned sometime after breakfast,

just as I was loading my daypack to hike up to Section Line

Lake. They had returned to our lake through the campsite formerly

occupied by the three frat boys, who had packed up and left

already. We never did find out which trailhead they used.

Nancy and Patricia decided to hike back to Mavis

on the Fox Ridge Trail, then take the Wolford Cabin Trail up

to the PCT and head west. Patricia had an older Forest Service

map that showed a little spur trail off the PCT dropping down

to Section Line Lake. My more recent map showed no such spur,

indicating that it was no longer maintained. I retold my tale

of the suicidal scramble down the cliff face to Section Line

Lake with Mr. Popper, but she and Nancy wanted to give the new

route a try. If the going got tough, they would turn back. In

the late morning they headed off.

I resolved to cross-country directly up to Section

Line Lake. Mr. Popper must have led us back that way 25 years

ago, and since I could remember nothing of the hike, it must

have been significantly uneventful. Barbara would stay behind

because her achilles tendon was acting up.

Barbara walked with me along a fisherman's

trail on the eastern shore to the big meadow at the southeastern

corner. There we crossed an inlet stream, which I presumed was

flowing out of Section Line Lake 500 feet above. We found a

large, empty campsite containing two stout trees with deep blazes.

I interpreted the blazes to be the gateway to the upper lake.

Up the slope I also found several cairns that looked like the

beginning of a trail. We had a leisurely lunch viewing the lake

from a new perspective. Barbara spotted a kingfisher she wanted

to keep an eye on.

Barbara walked with me along a fisherman's

trail on the eastern shore to the big meadow at the southeastern

corner. There we crossed an inlet stream, which I presumed was

flowing out of Section Line Lake 500 feet above. We found a

large, empty campsite containing two stout trees with deep blazes.

I interpreted the blazes to be the gateway to the upper lake.

Up the slope I also found several cairns that looked like the

beginning of a trail. We had a leisurely lunch viewing the lake

from a new perspective. Barbara spotted a kingfisher she wanted

to keep an eye on.

After lunch I clambered up the steep bluff and

found a faint use trail marked with sporadic cairns. Soon the

cairns ran out, so I followed the arrow on my GPS into which

I had programed the coordinates for Section Line Lake.  The

route was steep and brushy, climbing the eastern slope of a

broad, shallow canyon down which flowed a stream. I assumed

the stream was pouring out of Section Line Lake. The valley

floor became too overgrown to follow the stream directly, so

I climbed higher into the broken talus. The scramble was more

difficult than I expected.

The

route was steep and brushy, climbing the eastern slope of a

broad, shallow canyon down which flowed a stream. I assumed

the stream was pouring out of Section Line Lake. The valley

floor became too overgrown to follow the stream directly, so

I climbed higher into the broken talus. The scramble was more

difficult than I expected.

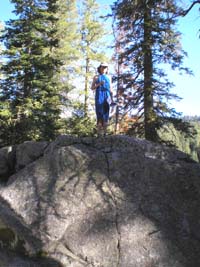

I was ascending a north-facing,

thickly forested slope. The GPS lost the signal as the satellites

dropped below the massif ahead, and thus kept pointing in the

same direction. Finally I topped a treeless ridge, balancing

in the middle of a field of sharp-edged granite boulders, and

got a fresh reading. I had missed the lake by only a couple

hundred feet, but the terrain was too rough to simply cut across

to the lake. I had to backtrack down to the duff of the forest

floor, traverse over to the right, and climb again. It turned

out the stream I was following was not flowing out of Section

Line Lake after all, but from a series of springs in a ferny

glade below the lake. I crossed above the springs, then headed

uphill again. It had taken me forty minutes to find the lake.

From the north ridge of the cirque above the

Section Line Lake, I called Barbara on the radio and told her

the climb had been rough going.  Then

I dropped down to the northwest shore (N 41 12' 088.9",

W 122 50' 41.6", 7065 feet). The lake was small and intimate

beneath a towering headwall, down which tumbled a swath of sharp,

white rock, pried loose by water freezing in the cracks and

seams of the granite cliff face. Enormous boulders pocked the

landscape, one near the outlet, which no longer flowed. The

green, rippling water was shallow near the north shore, but

plunged deep below the headwall. A healthy forest had gained

foothold in the rocky soil. The shore was bearded with low azalea,

heather, and grass, through which a faint fishermen trail wound

among the boulders.

Then

I dropped down to the northwest shore (N 41 12' 088.9",

W 122 50' 41.6", 7065 feet). The lake was small and intimate

beneath a towering headwall, down which tumbled a swath of sharp,

white rock, pried loose by water freezing in the cracks and

seams of the granite cliff face. Enormous boulders pocked the

landscape, one near the outlet, which no longer flowed. The

green, rippling water was shallow near the north shore, but

plunged deep below the headwall. A healthy forest had gained

foothold in the rocky soil. The shore was bearded with low azalea,

heather, and grass, through which a faint fishermen trail wound

among the boulders.

As I circled clockwise taking pictures, I became

aware of two young women on their hands and knees in the short

brush and heather beside the water on the southeast shore. They

were not sunbathing, but fully clothed, with broad floppy hats.

They were preoccupied doing something slowly, painstakingly.

Perhaps picking berries?

"Hello!" I called out from a hundred

feet away.

One sat up. "Hello." Her calm voice

carried nicely over the still water.

"Have you seen two women hiking down from

the crest trail?"

"No. You're the first person we've seen

today."

"Are you camped up here?"

"Yes," she replied. "Over in those

trees." She pointed to a small stand behind her, away from

the lake.

"Is there a trail up here?" I asked.

"Yes. A rough one. From Mavis."

I explained briefly that I was supposed to meet

Nancy and Patricia here. "If you see them, let them know

I was already here and gone."

"Okay." She went back to whatever she

was doing. Apprehensive, I approached no closer. Perhaps they

were up to something kinky. How would I know? There were more

things in this universe than what my philosophy encompassed.

I decided to let them have their space and turned back to retrace

my steps to the far shore. There I sat on a boulder for a while

and took a few more photos. Then I headed back down.

While I was away, Barbara

saw two young guys fishing, probably dayhikers, as she completed

her clockwise loop back to camp. She was relaxing at our campsite,

thinking all the dayhikers had left, when she was stunned by

three thunderous gunshots nearby, right at the lake. She scrambled

behind a boulder and kept her head down, her heart trip-hammering.

But there were no more shots, and she never saw who it was.

I called about fifteen minutes later to say I was almost down

to our lake, and that I, too, had heard the shots echoing through

the canyon. I saw no one on my way around the lake.

We walked over to the granite boulders near the

frat boys' campsite and swam off the rocks, then rested awhile.

It gave us yet another perspective. The weather was a little

cooler and windier than before, but plenty warm in the sun.

Nancy and Patricia got back around five. They

had arrived at Section Line after I left and talked with two

women camped there. They were doing a frog survey for Redwood

Sciences Laboratory. The frog populations of these lakes had

been decimated in recent years, probably because the Forest

Service had been stocking the lakes for years with non-native

fish. Now the stocking had stopped, and biologists wanted to

know if the frog population was coming back. (See Effects

of Introduced Fish on Native Biodiversity and Ecosystem Subsidy.)

What I had considered odd behavior, now made sense. The women

had been counting frogs.

A cairn had marked the cutoff trail from the

PCT. The hike down to Section Line Lake had not been difficult.

From Section Line they had come back to camp a different way

than I. We all agreed that it was steep and rough no matter

which way you go.

We had Fox Creek Lake all to ourselves. Nancy

chose to deploy her tent for the final night. "As long

as I carried it up here," she said. I recognized it as

the old one-person tent Mr. Popper had crawled into years ago.

She had inherited it. The next morning she would tell us, "It

was like sleeping in a sarcophagus."

It was pleasant again to sit around the fire

with the whole tribe and watch the stars come out. We finished

Patricia's rum. The tequila and amaretto we would carry out.

That night was cold enough for me to zip up my bag, even with

the tent fly on.

Monday morning we left around eleven, stopping

at the outlet to watch a Cooper's Hawk chasing Barbara's kingfisher.

We did not stop at Mavis Lake. If Barbara has taught me anything

over the years, it is the hollowness of peak bagging. Or lake

bagging. Just to say you have been there. For all I could remember,

I may have been to Mavis twenty-five years ago. I cannot

recall, and it doesn't matter.

The

return trek through the beautiful moraine terraces was particularly

agreeable. After a while, though, the downhill trudge became

wearisome, as it always does. For me this backpack had renewed

old acquaintances. With the lakes. With the route. With Mr.

Popper. With Nancy. With Barbara. With myself. As usual, I was

not the same person who had hiked in. But was I any wiser? Probably

not.

The

return trek through the beautiful moraine terraces was particularly

agreeable. After a while, though, the downhill trudge became

wearisome, as it always does. For me this backpack had renewed

old acquaintances. With the lakes. With the route. With Mr.

Popper. With Nancy. With Barbara. With myself. As usual, I was

not the same person who had hiked in. But was I any wiser? Probably

not.

Just beyond the wilderness boundary sign a single

car was parked on the first dirt road crossing the trail, just

above the hot, steep, exposed final descent. We figured it probably

belonged to the two women at Section Line Lake. When I planned

the trip, a ranger had told me about a jeep road that ends right

there at the boundary, cutting off a quarter mile of steep uphill.

But we had been in too much of a hurry to look for it.

Ours were the only cars parked at the trailhead.

The sun was blazing hot. Nancy and Patricia had beaten us back

by fifteen minutes, and they were ready to move on. Nancy wanted

to drive in to Etna and get her spare tire repaired. Since we

planned to head north to our cabin through Etna anyway, we agreed

to look for them there.

We found Nancy and Patricia at the gas station

on Highway 3 on the outskirts of town. They had searched for

a garage to fix the flat, but couldn't find anyone to do the

job. So they bought a can of "Fix-a-Flat" at a hardware

store and were heading for home. We bid each other farewell

and went our separate ways.

Return to Backpacking

in Jefferson