Garden at the Top of the World

Copyright © 2003 by Richard S. Platz

All Rights Reserved

Little Duck and Eaton Lakes Backpack

Russian Wilderness

June 28, 2003, to July 3, 2003

Big ants, small ants forage

In the garden of the Buddhas

Puzzling over maps and hiking books, telephoning ranger stations,

and consulting computerized topo maps, I worried over our next

destination as if it were key to solving the Grand Unification

Theory. In the last week of June Barbara cut to the heart of the

matter by scrawling "Duck Lake?" on a small,

square, yellow Post-It label and sticking it on my place mat at

the dinner table.

Amidst a heat wave, with temperatures in Blue Lake in the high

90's, we prepared for backpacking to Duck and Eaton Lakes. Mid-day

on Saturday we left in our newly reconditioned (and air-conditioned)

van, had lunch at Cinnabar Sam's in Willow Creek, and refueled

in Weaverville. On a hairy curve on Highway 3 going up Scott Mountain

we pulled over to help a fellow motorist. With two blown tires

his car straddled the rocky shoulder, half on and half off the

road. Had we not ourselves recently received similar aid, we would

no doubt have passed by this pudgy fellow in his effeminate black

silk shirt. Even so, Barbara hung back, smelling an incipient

ambush. Unsurprisingly, there was no cell phone service. The man

eschewed my offer for a ride, preferring to stay with his worldly

possessions, all of which seemed to bristle from his disabled

vehicle. So we offered instead to phone the Highway Patrol for

him from Callahan.

Into the twilight of Callahan's only bar we stepped like pilgrims

into a den of brooding outlaws. The patrons eyed us warily as

we explained our need to borrow a phone to call the CHP, then

immediately fell to debating the merits of our proposal. "It'll

take'em three hours jus' t'git there," one argued loudly,

to which others assented or disagreed in accordance with their

current mood. Everyone had an opinion, but no one lifted a hand

to do anything other than order another round. The consensus was

to send "Dick" out to help the stranded motorist, but

no one appeared willing to actually pick up the telephone and

call this Dick, or even disclose to us his whereabouts.

So we withdrew, headed up the road to Etna, and dialed 911 from

a pay phone outside Bob's Ranchhouse. Crossing Scott Mountain

Summit had apparently thrown us into a discordant Highway Patrol

dimension. Solving problems from another district was not in this

dispatcher's job description, so it took some cajoling to get

her to check with the Susanville district. Someone, it turned

out, had already called. An officer was on the way.

Our civic duty discharged, we ate dinner at Bob's, one of Barbara's

favorite eateries. After dinner, we headed back south toward Callahan,

then turned off and followed French Creek Road southwest as it

climbed towards the Russian Wilderness. The trailhead eluded us

at first. Someone had removed signs at a few of the critical crossroads,

perhaps for souvenirs, or to keep the trailhead a secret, or simply

out of pure vandalism. I pulled out the eTrex G.P.S. receiver,

into which I had entered the coordinates of the parking area,

and we reversed our direction and homed in on the trailhead. Soon

we pulled into a large, flat, graveled area with the trailhead

sign at the far end and two vehicles crowded nearby, a full-sized

pickup and a small wagon.

The G.P.S. reported the trailhead to be at an altitude of 4470

feet. The federal government, we knew, intentionally introduced

fuzziness into the altitude coordinate to throw terrorists off.

Art Bernstein reported the trailhead to be 4800. In either case,

Little Duck and Eaton Lakes lay roughly 2000 feet above us. We

would spend the night in the van and backpack in the next morning.

As we were moving things off the bed in the van, a young woman

in her twenties hiked in from the trail, heaved off her backpack,

and dumped it into the back of the pickup. In response to our

inquiries, she told us that she and her friends had been at Big

Duck Lake, and the only others there were her parents, who planned

to hike out tomorrow. I asked if she knew whether anyone was camped

at Little Duck Lake, and she responded, "My father hiked

over there and said it was full."

Her cryptic response seemed odd, since the only two cars at the

trailhead belonged to her and her parents. Whence came all the

other campers? Could they be horse-packers from Paynes or Horse

Range Lakes?

Before we could puzzle it out, a second young woman labored in.

"Thank fuckin' God!" she snorted and dropped

her pack in the dirt beside the truck.

A moment later she was followed by a young man, his unstuffed

sleeping bag draped like a halter over his pack. "That,"

he proclaimed, arms dangling at his sides, apparently too tired

to remove his backpack, "is a hard hike!"

They quickly wrestled their backpacks into the bed of the pickup

truck, then climbed into the station wagon and drove off. I walked

over and examined their equipment strewn about the truck bed,

open to the whole world, vulnerable to thieves and pirates. Ahrrr,

trusting souls they be. The gear was low-tech and heavy, as

if picked up hastily at K Mart or a garage sale. The sleeping

bags lay draped unstuffed over the packs.

We stretched our legs by walking up the road until we could view

Mount Shasta. We saw a tanager. Planning an early start for cool

morning hiking, we packed our backpacks as much as we could before

bedtime.

Sunday morning we awoke at 5:30, ate a quick bowl of oatmeal,

and were on the trail by 7:15. From the beginning the hike was

very steep going, but at least the tall forest provided shade.

The trail started up the rocky tread of an abandoned logging road,

then switched-back up a granitic moraine, crossing, but not following,

several logging roads of more moderate grade that once provided

access to two higher trailheads, now permanently closed. At one

road crossing we encountered the wilderness boundary sign planted

like a grave marker in the yellow dirt. At the third or fourth

crossroad, the trail hair-pinned left and followed its more level

grade south, winding into an ever deepening woods. Here we could

walk side-by-side, occasionally skirting a water bar or washout

that rendered the route impassable to motor vehicles, and breathe

in the ambience of the forest.

Our first rest stop was the Eaton Lakes trail junction at 5655

feet, which a few years ago had been the highest parking area

for both the Eaton and Duck Lakes trailheads. Having already climbed

a thousand feet, we happily set down our packs and stretched.

Across gurgling Duck Lake Creek we saw the trail which would contour

a half mile around the mountain, then shoot straight up an impossible

staircase of loose granite scree to Eaton Lakes. A hundred feet

further up the road was the turnoff to the Duck Lakes. The road

itself continued on to Horseshoe Lake, which we remembered to

be a hot, daunting, and marginally rewarding trek. As we pondered

between Eaton and Duck Lakes, a father and small son passed us,

heading up to Duck Lake for the day to fish.

Then the parents of the girl we had debriefed at the parking

lot stopped to chat on their hike out. We again asked about Little

Duck Lake, and the father said no one was there. That's not what

his daughter had told us. On further questioning, he explained

that his statement to his daughter meant the lake was full

of water, not that the campsites were full of people. We

had a good laugh at the misunderstanding. We mentioned the gear

laying unattended in the back of his pickup, and he said he never

had a problem. People didn't steal things around there.

We

had been unsure which lake to visit first, but now decided definitively

on Little Duck. The trail climbed steeply through the thick forest

along the west slope of the drainage. Almost immediately we encountered

huge trees, blown down by the wind, blocking the trail. Each one

required an off-trail scramble up and around on the slippery duff

and vegetation of the steep bank, a task made more precarious

by the high balance of our backpacks. The trail soon eased a bit

as we entered the cathedral of Duck Creek's upper valley. A forest

of red fir, western white pine, mountain hemlock, and an occasional

Brewer spruce supported a high vaulted ceiling above the U-shape

valley into which little sunlight penetrated. Through a valley

floor strewn with boulders and logs left by the high water and

snow of innumerable Springs, the trail wound up the moraine on

the west side of the creek. At least thirteen other conifer species

are also reputed to be found in Duck Creek's Special Interest/Botanical

Area. We were too tired to care. Sweating and puffing, we wondering

why this leg always seemed so much longer than the map allowed. We

had been unsure which lake to visit first, but now decided definitively

on Little Duck. The trail climbed steeply through the thick forest

along the west slope of the drainage. Almost immediately we encountered

huge trees, blown down by the wind, blocking the trail. Each one

required an off-trail scramble up and around on the slippery duff

and vegetation of the steep bank, a task made more precarious

by the high balance of our backpacks. The trail soon eased a bit

as we entered the cathedral of Duck Creek's upper valley. A forest

of red fir, western white pine, mountain hemlock, and an occasional

Brewer spruce supported a high vaulted ceiling above the U-shape

valley into which little sunlight penetrated. Through a valley

floor strewn with boulders and logs left by the high water and

snow of innumerable Springs, the trail wound up the moraine on

the west side of the creek. At least thirteen other conifer species

are also reputed to be found in Duck Creek's Special Interest/Botanical

Area. We were too tired to care. Sweating and puffing, we wondering

why this leg always seemed so much longer than the map allowed.

It was late morning before the trail crossed over to the creek

and we came at last to the junction to Big Duck Lake. Signs nailed

to a tree pointed to Big Duck, across the creek, and Little Duck

on up the Valley. We stopped for a break. My lateral malleolus

was bothering me. Mosquitoes quickly sniffed us out, and we had

to slap on bug juice. The easy trail to Big Duck, rising out of

the forest into blindingly white granite boulders, was tempting.

Big Duck's waters lay only a half mile away and less than two

hundred feet up. Little Duck was still at least a mile away and

a five hundred foot climb.

But we had already camped once at Big Duck, and we both remembered

Little Duck to be the more attractive lake. Besides, fewer people

were likely to camp at Little Duck. So after a breather, we pressed

inexorably on. The trail soon rose out of the forest, became difficult

to follow as it wound across a high divide of bright granite bedrock,

then dropped back into the forest of the shallower upper valley

just below Little Duck Lake.

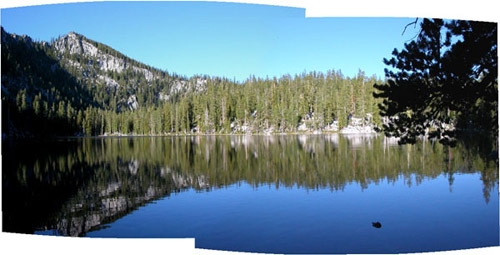

We

arrived for lunch after climbing somewhere between 1900 and 2300

feet (depending on the dubious altitude of the trailhead). Little

Duck Lake sits in a forested steep granite cirque at 6700 feet

just beneath the spine of the Russian Peak Pluton dividing the

Scott Valley from the Russian Creek drainage to the southwest.

Snow crowned the north face of the ragged ridge just south of

the lake and reached all the way down to water's edge, with impressive

waterfalls high on the granite cliffs. We

arrived for lunch after climbing somewhere between 1900 and 2300

feet (depending on the dubious altitude of the trailhead). Little

Duck Lake sits in a forested steep granite cirque at 6700 feet

just beneath the spine of the Russian Peak Pluton dividing the

Scott Valley from the Russian Creek drainage to the southwest.

Snow crowned the north face of the ragged ridge just south of

the lake and reached all the way down to water's edge, with impressive

waterfalls high on the granite cliffs.

The weather was warm, but windy. We chose a campsite in the wildly

mixed conifer forest beside an outcropping of glacier-polished

granite that formed the northeast shore of the lake. We identified

western white or white bark pine, Ponderosa pine, sugar pine,

lodgepole pine, mountain hemlock, Brewer spruce, and red fir.

Phlox, shooting stars, and snow plant added a touch of color to

the patchy ground cover.

I

dove in for a swim while Barbara waded in the shallow beach of

granite sand. The water was cold, but not unbearable. Doggedly

we set up camp, built our fire, ate a freeze-dried dinner, and

washed up. An osprey fished while a tanager flitted through the

branches and juncos foraged. From our hammocks we heard mountain

chickadees, a nuthatch, a Steller's jay, and, further away, an

owl and a woodpecker. Later we sat by the water until the bats

came out. Oddly, we saw no deer or rodents, although we did hear

something small steal away with a food bar wrapper. We turned

in early. I

dove in for a swim while Barbara waded in the shallow beach of

granite sand. The water was cold, but not unbearable. Doggedly

we set up camp, built our fire, ate a freeze-dried dinner, and

washed up. An osprey fished while a tanager flitted through the

branches and juncos foraged. From our hammocks we heard mountain

chickadees, a nuthatch, a Steller's jay, and, further away, an

owl and a woodpecker. Later we sat by the water until the bats

came out. Oddly, we saw no deer or rodents, although we did hear

something small steal away with a food bar wrapper. We turned

in early.

Monday morning we awoke to beautiful weather, not too hot, and

just windy enough to keep the bugs away. We boiled water, prepared

our morning cups, then sat on the smooth granite slab at water's

edge.

I sipped my mocha coffee and watched a black ant crawl up a dead

pine snag, trying one branch stub, turning back at its dead end,

climbing, trying another, foraging fruitlessly. No blame. If souls

transmigrate, why would they not do so outside the illusion of

time? Why must one be reborn later in time? Why not earlier?

Or at the same time as one's other incarnations. Perhaps

for all incarnations, there is but one soul. Parallel

reincarnation. Is this what is meant by the oneness of the Buddha?

Perhaps this is the root of all compassion: we are in fact

all one. Hurting or killing a sentient being is hurting or killing

oneself. I am the ant foraging up the dead pine snag.

Slapping a mosquito, I was expelled rudely from Buddhism back

into the Judeo- Christian world of Good and Evil. Evil may be

destroyed. Must be destroyed. Our elected leaders, those

darlings of the Christian right wing, declare what is Good and

what is Evil with the conviction of divine revelation. Our military

might is unleashed to overthrow Evil. Root it out. Crush it. Collateral

damage is unavoidable in the crusade for Good.

Westerners

criticize Buddhism as a "do nothing" world view, which

allows Evil to flourish. What they do not see is that Good and

Evil are in the eye of the beholder. The Evil they rage against

and the Good they embrace both arise, figuratively and literally,

from a vision already distorted by that biblical dichotomy. But

to an undistorted eye, to a compassionate eye, are not Good and

Evil just two different views of the same thing? Westerners

criticize Buddhism as a "do nothing" world view, which

allows Evil to flourish. What they do not see is that Good and

Evil are in the eye of the beholder. The Evil they rage against

and the Good they embrace both arise, figuratively and literally,

from a vision already distorted by that biblical dichotomy. But

to an undistorted eye, to a compassionate eye, are not Good and

Evil just two different views of the same thing?

Motionless on a stone seat nearer the water, Barbara, by contrast,

became the Buddha. Unaware of my internal babble, she drank

her green tea quietly. Her discursive mind quieted. At one with

nature, she beheld the reality-unreality of being there

completely at the water's edge. Beyond words.

Late

that morning we hiked sluggishly up the slope above our campsite

as far as the steepening valley wall safely allowed. From the

sparsely forested granite mountainside we could look out over

both Big Duck and Little Duck Lakes and beyond our cirque to Mt.

Shasta's snowy summit in the distance. The Duck Creek valley curved

down and away to the northeast to join French Creek. Beyond the

forested slope above Big Duck Lake rose the spires of Eaton Peak,

and we looked for a shortcut up to Eaton Lakes, which would save

us a thousand-foot descent to the Eaton Lakes trailhead and a

thousand-foot climb back up to the lakes. But from our vantage,

no easy route was obvious across the rough terrain of steep granite

slopes. Late

that morning we hiked sluggishly up the slope above our campsite

as far as the steepening valley wall safely allowed. From the

sparsely forested granite mountainside we could look out over

both Big Duck and Little Duck Lakes and beyond our cirque to Mt.

Shasta's snowy summit in the distance. The Duck Creek valley curved

down and away to the northeast to join French Creek. Beyond the

forested slope above Big Duck Lake rose the spires of Eaton Peak,

and we looked for a shortcut up to Eaton Lakes, which would save

us a thousand-foot descent to the Eaton Lakes trailhead and a

thousand-foot climb back up to the lakes. But from our vantage,

no easy route was obvious across the rough terrain of steep granite

slopes.

After lunch we hiked leisurely around Little Duck Lake and found

good campsites on the north side and at the inlet. On the south

side of the lake we crossed on boulders high up the slope to avoid

the snow. When we got back to camp, we jumped in for a short,

invigorating swim. Later we hiked down the trail, but not far

because the mosquitos came out as the day cooled and the wind

died down. The entire stay at Little Duck Lake we saw and heard

no one else.

On Tuesday we arose fairly early to sit, eat breakfast, and break

camp. On the trail by 9 AM, we hiked down and down through Duck

Creek's tall forested valley, failing utterly to notice the junction

with Big Duck. Inattention thus saved us from attempting a cross-country

maneuver from Big Duck to Eaton. Again we skirted the blown-down

trees and dropped to the logging road at the old trailhead.

We stopped briefly at the Eaton Lakes trail junction, then boulder-hopped

across the stream to begin our climb to Eaton Lakes. At first

the route was wet and muddy, then hard to follow through a maze

of small blowdowns until it rose out of the swamp to cross exposed

bedrock. This segment was lovely as it contoured through the open

forest. Before long the trail took a sharp right turn and climbed

a series of steep logging roads gouged into the glacial till,

then straight south up the spine of a long, exposed moraine. We

could not find the "trail" sign we had missed the last

time we hiked down from Eaton Lakes and could not agree where

we had taken our wrong turn. As the moraine finally joined the

main bulk of the mountain, the trail began to switchback up the

impossibly steep mountainside through a dense forest of predominantly

red fir. Soon we began to encounter blown down trees blocking

the trail. One after another we clambered over, under, or cross-country

around a dozen downed or deeply nodding trees, many rare Brewer's

spruce. Off-trail, the slope was steep and dangerous. Progress

became laborious, and our pace slowed. Our backpacks grew heavy.

We were soaked with sweat. Stopping at last for a breather on

an open slash of granite talus, we heard gurgling beneath the

sharp white rocks the beginning of French Creek as it flowed down

from lower Eaton Lake.

As

we finally approached the crest, the trail splintered and grew

vague. Apparently all routes led to the lake. Barbara followed

the most prominent track and at long last the waters of the larger

Eaton Lake glistened in the sunlight. We followed the main path

past several small campsites to the largest campsite near the

water's edge. Exhausted, we decided a swim would help revive us.

From a sloping slab of granite we plunged into the shallow waters

of a cove near the outlet. The water was warmer than at Little

Duck, probably because snow did not reach down to lake level here. As

we finally approached the crest, the trail splintered and grew

vague. Apparently all routes led to the lake. Barbara followed

the most prominent track and at long last the waters of the larger

Eaton Lake glistened in the sunlight. We followed the main path

past several small campsites to the largest campsite near the

water's edge. Exhausted, we decided a swim would help revive us.

From a sloping slab of granite we plunged into the shallow waters

of a cove near the outlet. The water was warmer than at Little

Duck, probably because snow did not reach down to lake level here.

The campsite we chose was a fine one, with a level

tent site, a nice fire ring capped with a broad flat rock, and

hammock trees at the water's edge. Along the bank grew wild roses,

miniature azaleas, and patches of shrubby alder. Between our tent

and the water, silver-gray logs fallen in seasons past lay crisscrossed

like pick-up sticks. At Little Duck Lake the high ridge had blocked

the sun by seven in the evening, but here, at the top of the world,

the sun would shine on the lake until it set around nine. Lots

of brewer spruce, yellow rumped warblers, and granite boulders

eroded into giant "pillows" helped to make this one

of our favorite destinations. During our entire stay, no other

human intruded to break the spell.

We climbed the sandy slope to the ridge above our campsite in

search of the Zen garden I had happened upon during our previous

visit. At the crest, I found the stone Buddhas. Rains and snows

of countless seasons had washed away the granite sand of the moraine,

exposing huge boulders, by glaciers ground and rounded and by

dripping water carved, which now sat in an open garden of gently

sloping sand and manzanita like forgotten Henry Moore sculptures.

Or, more appropriately, like massive Buddhas at the Ryoanji

Temple in Kyoto.

Tall ponderosa pines and red firs, nodding Brewer's spruce and

mountain hemlock, whitebark pines, and a few stark white snags

rose like temple columns. To the east lay the Scott Valley and,

in the distance, Mount Shasta. To the southwest Eaton Peak's rugged

spires and cleavers pierced the pure blue sky, its granite shoulders

so white that snow banks hid in the bright sunlight, and its glacial-polished

arms reaching down to cradle the emerald waters of Eaton Lakes

in a peaceful mudra. A fish jumped from the wind-rippled water.

Below the surface near the sandy shore glowed the bones of fallen

trees and a jumble of granite slabs plunging away to impenetrable

depths. Gentle gusts from every direction kept the bugs away.

Black ants, large and small, foraged peacefully in the coarse

sand. An occasional bee buzzed past.

That night we slept well.

On Wednesday morning, as we sat in our hammocks sipping tea and

coffee, a hummingbird roared in to investigate my red rope, then

rattled away. Fish circled in the shallow water, leaping into

the air in acrobatic back-flips. Insects droned in the flowers.

A sudden blast of wind would ripple across the lake, disperse

the bugs, then retreat through the branches. Trees grew in stillness.

The sky was achingly blue.

Watching patiently through her new binoculars, Barbara spotted

a mountain chickadee, a yellow rumped warbler, and a woodpecker.

The woodpecker was unusual, with white head, a red patch on the

back of the head, and a large white patch on the outer part of

the wing. We later found out it was a white-headed woodpecker,

found in mountain pine forests of the Pacific states.

After

breakfast we hiked around the lake clockwise from our campsite

on the north end. The going was not easy. The trail hugged the

shore on the east slope, except for a few rough scrambles over

steep rock falls. Just before reaching the inlet stream from the

upper lake, we found one not-so-great campsite. The narrow isthmus

between Upper and Lower Eaton Lakes was bouldery and brushy with

no apparent trail. We fought our way through to the upper lake,

which was shallow and small, but ruggedly beautiful. The shore

was a heap of huge jagged boulders, broken away from the peak

above. A few sat in the water as islands. No level tent site was

apparent in the thick undergrowth. After

breakfast we hiked around the lake clockwise from our campsite

on the north end. The going was not easy. The trail hugged the

shore on the east slope, except for a few rough scrambles over

steep rock falls. Just before reaching the inlet stream from the

upper lake, we found one not-so-great campsite. The narrow isthmus

between Upper and Lower Eaton Lakes was bouldery and brushy with

no apparent trail. We fought our way through to the upper lake,

which was shallow and small, but ruggedly beautiful. The shore

was a heap of huge jagged boulders, broken away from the peak

above. A few sat in the water as islands. No level tent site was

apparent in the thick undergrowth.

Continuing along the fisherman's trail we came to a very good

campsite on the west shore. In the tall forest stood a huge fire

ring and several level tent sites. It had the look of a horse

camp, and, indeed, we scuffed through traces of ancient horse

manure. This we found odd. To get a horse in there would require

either the difficult circumnavigation of three-quarters of the

lake, as we had just done, or crossing a rugged boulder field

and outlet stream from our camp. Or was there another explanation?

After lunch we followed a vague track winding up the hillside

above the horse camp. The going was rough and the path less than

obvious, perhaps only a game trail. From the top of the moraine

above the lake the vague tread seemed to lead on to the west,

to dip into a shallow valley and then, perhaps, to rise toward

the next ridge. Beyond that ridge lay the Duck Creek drainage.

With the thrill of Vasco da Gama as he first rounded the Cape

of Good Hope, we wondered if perhaps we had found the elusive

direct route between Big Duck and Eaton Lakes. Horses might be

able to cross-country from Big Duck Lake to this horse camp without

crossing the boulder field at the Eaton's outlet.

We, however, did have to cross the boulder field to complete

our hike around the lake. Here the boulders were not the gentle

pillow shapes of the Buddha garden, but were huge and sharp-edged

and jumbled as if freshly severed by a colossal axe from Eaton

Peak far to the south. Unlike the boulders ground round and smooth

by years of churning within the glacier, these seemed to have

been transported intact by some other geological process. Maybe

they once formed a subterranean outcropping of the granitic bedrock

and were fractured in place by freezing and thawing, then washed

clean by periodic flooding from the lakes. More likely they had

recently splintered off Eaton Peak and slid down the face of a

glacier or snowfield blanketing the lakes. In any case, the going

was extremely difficult across steep slab faces with keenly honed

edges and great gaps and hollows into which a foot could slip

and a leg be broken. There appeared to be no alternative route

short of going back. Finally at the end of the boulder field,

we crossed the outlet stream through thick pine mat manzanita,

blindly probing for solid footing amid the logs and holes and

rare patches of solid ground.

We returned to our camp to find a hole chewed in the water filter

tubing, just like at Square Lake the year before. Damn the

fuzzy little ground squirrels! Fortunately the hole was near

an end, and as our field repair we simply sliced off the bad part

and reattached the hose. After a bracing swim in the deep water

on the east side of the lake, we strolled up to the rock garden,

then climbed the ridge above it to get a clearer view down into

Scott Valley.

Thursday we were up early to watch the morning shadows shorten

over the lake, saddened to be leaving such a lovely place. We

broke camp and were on the trail by nine. The descent was steep.

Hiking down slope is always more precarious than climbing up,

testing different muscles. Overbalancing or slipping on loose

scree can have more serious consequences going down. The same

fallen trees had to be climbed, ducked, or tediously skirted.

At the junction of a spur logging road on the long exposed moraine

we finally spotted the tiny "trail" sign we had missed

on the way up and on the way out last time. The hot sun bore down.

The final descent seemed endless. It took three hours to drop

the 2000 feet to the van.

Besides our own, two Forest Service vehicles sat in the parking

lot. Maybe the rangers were clearing deadfalls off the trail to

Little Duck Lake.

As we sat in our folding chairs in the shade of the kiosk, wiping

off the sweat and sorting through our belongings, a car raced

in and two young men rushed over to the map. They wanted to fish,

they told us, and were annoyed that they could no longer drive

in on the old road to get closer to the lake. After a brief consultation,

they hoisted their fishing poles and without water or day packs

began the trek in to Big Duck Lake for the day--starting at noon!

They had no clue how long and hard a hike it was going to be.

Return to Backpacking

in Jefferson

|