Shoshone

Mike's Stronghold

Copyright © 2005-07

by Richard S. Platz, All

rights reserved

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Little High Rock Canyon Backpack

Little High Rock Canyon Wilderness

Black Rock Desert National Conservation Area

June 4-12, 2005

"Road signs riddled with bullet holes"

In the Spring of 1868 the transcontinental railroad

dragged its greasy belly down from the High Sierra and crawled

east across the high desert basin toward Promontory Point. Whores,

gamblers, pistoleros, and swindlers of every ilk, smelling opportunity,

dropped like ticks off the clanking beast at the newborn town

of Reno on the Truckee River in the Nevada territory. Their

prey were the miners and merchants of the Comstock Lode in Virginia

City and Gold Hill and emigrants still jarring along the California

wagon trails. Thus were sown the seeds of Nevadan character.

Reno and Sparks have since grown into a turbulent

cesspool of mindless development, swamping the Truckee River

Valley with high-rise casinos and shopping malls, factories,

freeways, and low rent housing, and overflowing into adjacent

desert valleys. Manifest destiny has gone mad. With an atavistic

frenzy the inhabitants still embrace legal prostitution, gambling,

and firearms. Jeep tracks and mine tailings scar the desert

and surrounding hills. Road signs are riddled with bullet holes.

Ah, but to the north of this madness lay the territory

we longed to visit, where the tap root of frontier mind draws

sustenance from the austere alkali playa of the Black Rock Desert.

The place has been popularized by the Burning Man Festival,

which blooms and fades like a desert flower one week each September.

But we wanted to go there not because Burning Man would be

there, but because it would not. We wanted to see the

land with cattle and sheep as its sole inhabitants. When no

traffic would meet us on the dusty gravel byways. We wanted

to see the land as it was seen from a Conestoga wagon following

the Lassen Trail.

Much we did not know about that remote

landscape and what grew there. How the Nevada desert nourishes

a depraved twist of mind. Where genocide is labeled "frontier

justice." Where long after the Indian Wars concluded elsewhere,

the Sheriff of Elko County urged citizens to "kill all

the Indians, and every Indian that may be found roaming the

Idaho country." (Twin Falls Times, Thursday, May

12, 1910.) Where as recently as 1911 a posse hunted down and

savagely massacred an impoverished band of Paiutes. All but

four children. For we had not yet heard of Shoshone Mike.

Unspoiled wilderness is not something the Nevadan

mind holds in high regard. Hell, spoiling things is half the

fun! So it came as a shock when Congress, in the last days of

Clinton's Presidency in 2000, designated three-quarters of a

million acres as wilderness in the Black Rock Desert, High Rock

Canyon, Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area. Now that

the land was liberated from off-road vehicles spewing beer cans,

bullets, and country music, we wanted to explore there. The

first week of June 2005 gave us a perfect opportunity. Weather

forecasts called for scattered showers and thunderstorms and

temperatures fifteen to twenty degrees below normal. Perfect

desert weather, we decided.

Gerlach, Nevada, would be our portal into the

Black Rock Desert. Two roads led thither from Cedarville in

the Surprise Valley of Northeastern California. East, just across

the Nevada line, unpaved County Road 34 wound south from Vya

through the scenic desert hills. But we were in a big hurry

to get to Gerlach and get started, so we chose instead

the faster two-lane blacktop of Highway 447 as it traced the

valley south. We had no idea we would be seeing plenty of Road

34 before long.

Gerlach squats at the waist between two merging

deserts, the Black Rock to the northeast and the Smoke Creek

to the southwest. There a spring seeping from the base of the

Granite Range provided water and forage for pioneers taking

Noble's Cutoff on the Applegate Trail. The town later became

a watering stop for thirsty steam locomotives on the Western

Pacific Railroad. Diesels now pull long freights through town

without slowing.

Expecting little, we were yet disappointed. Gerlach

has no general store. No gas station. No museum. No roadside

attraction. Just a crossroads with a few featureless houses,

beached like dead whales on the edge of the vast alkali playa

and dusted a ghostly white. Two businesses were open. One was

a gloomy casino, cafe, and windowless motel called Bruno's,

the other the local office for the Burning Man. A kiosk beside

the old railroad water tower offered a terse BLM pamphlet warning

travelers in the National Conservation Area of muddy sinkholes,

blown tires, and death by dehydration.

The only store was at Empire, seven miles further

down the road on the other side of the desert. As we crossed

the playa on the ribbon of two-lane, a primordial terror crept

like a spider across the back of my mind. The featureless sweep

of vast white space overwhelmed reason. But the panic receded

with the playa, and we pressed on to Empire, company town of

the Empire Gypsum Company, where we ate sandwiches, purchased

supplies, and topped off our water jugs. It was time to make

a decision.

We had been able to find scant literature on the

Black Rock Wilderness. Wilderness, as defined by the federal

government, does not sit well with the Nevadan temperament.

Unlike the Desolation and South Warner Wildernesses nearby in

California, no permits are required in Nevada, no trail maps

or descriptions available, and no fire or use rules published.

No road signs point to wilderness access. Trailheads are unmarked.

Parking is not designated. Even wilderness boundaries are unclear.

Cell phones and weather radios are worthless. Our GPS, an old

pre-wilderness Sierra Club guidebook, and contour maps were

all we had to go on.

Arbitrarily we agreed on the first hike in the

guidebook, a climb up McGill Canyon toward 8850-foot King Lear

Peak in the Jackson Mountains rimming the Black Rock Desert

on the northeast. There would be no trail, but we could find

and follow McGill Creek as we climbed and camp along the stream.

It looked like about a 75-mile drive on gravel roads. We headed

back toward Gerlach, then, before recrossing the playa, turned

north on the gravel Road 2048 signed "Trego Hot Spring

17 mi."

The road started out fine, rising and falling

through the foothills above the playa, roughly paralleling the

BNSF railroad tracks. But soon the surface became rough with

sharp-edged rock. I slowed down to protect the tires. Little

black spots on the road seemed to be hopping and crawling toward

the playa. I tried to blink the spots out of my eyes. "Do

you see things crawling across the road?"

Barbara squinted through the windshield. "Are

they moving?"

We topped a rise, and the road was covered with

hundreds of them. Thousands. "What the hell are

those . . . things!" I screamed.

I slowed the van and Barbara leaned out the window.

They looked like giant crickets, maybe two inches long. Too

fat to fly.  The

creepy black-brown insects flowed west across the road in disorienting

waves. Our skin crawled. Giant nuclear mutant bugs were breeding

in the desert. Maybe feeding on tourists. We dared not stop.

The

creepy black-brown insects flowed west across the road in disorienting

waves. Our skin crawled. Giant nuclear mutant bugs were breeding

in the desert. Maybe feeding on tourists. We dared not stop.

Later we learned the little buggers are called

Mormon Crickets. Not true crickets, they are shieldbacked katydids,

and not the least carnivorous. In June of 1848 millions of the

insects began to devour the crops of Utah pioneers. Settlers

fought them without success and faced starvation. Then, in the

"Miracle of the Seagulls," a white cloud of California

gulls descended, gorged themselves on the crickets, threw up,

and ate more, until the crops were saved. Can you say hallelujah!

Apparently they are now a plague on the town of Empire. Prayer

has so far proved ineffectual.

After a few miles the infestation thinned. Soon

the bugs disappeared altogether. Our top speed was still only

25 mph, but the odometer told us we were approaching Trego Hot

Spring. We thought we might test the waters there, maybe even

spend the night and carry on to McGill Canyon the following

morning.

There were, of course, no roadsigns. Occasionally

parallel tire tracks would wander off into the sagebrush on

the right or down to the playa on the left. But none were signed.

The day was too warm to see steam rising from the hot spring.

No other vehicle passed us. In a moment of inspiration, I plugged

the GPS into the laptop, which found our road on the electronic

topo map. Barbara watched the blinking cursor move along the

road and called directions for turns. Unfortunately, the location

of the hot spring on the topo map was off by a quarter mile.

For a testy moment we considered, then dismissed the bumpy track

into the sage indicated by the map. Instead we followed well-worn

tire tracks to the hot spring (N40 46' 18.1", W119 07'

02.4").

Ah, this was what we

were here to experience. Surrounded by miles and miles  of

uninhabited sagebrush and desert playa, we had Trego Hot Springs

all to ourselves. Forty feet from the railroad track, 200-degree

water bubbled up into a pool that fed a long trench. There it

merged with cooler water, then spread out into a green oasis

of reeds and rushes. A "T" of welded iron rail at

the center of a flat area marked the Emigrant Trail, where pioneers

had once set off toward the Black Rock in the middle of the

desert, trusting there to find the next spring.

of

uninhabited sagebrush and desert playa, we had Trego Hot Springs

all to ourselves. Forty feet from the railroad track, 200-degree

water bubbled up into a pool that fed a long trench. There it

merged with cooler water, then spread out into a green oasis

of reeds and rushes. A "T" of welded iron rail at

the center of a flat area marked the Emigrant Trail, where pioneers

had once set off toward the Black Rock in the middle of the

desert, trusting there to find the next spring.

As we were unloading the van in the middle of

the broad flat, we heard the growl of approaching motors. Three

full-sized pickups, each with a hulking camper overbalanced

on its back, rocked and trundled up the alkali road. One by

one the campers parked alongside our van, and three middle-aged

couples unfolded themselves stiffly from the cabs. Barbara,

being amicable by nature, engaged them in conversation.

I was too miffed to join in. This was trailer-park

mentality at its worst! Four vehicles huddled together in

the vast desert emptiness as if circled against some hallucinated

Indian menace. I promptly began tossing chairs and tables back

into the van to by god find a more remote site. Sensing my mood,

Barbara let me go. For fifteen minutes I tried one place after

another, driving in widening circles in a futile attempt to

escape. I was growing increasingly homicidal when at last I

pushed the van around the end of the hot spring and up a rough,

narrow path to a bare patch of ground 300 feet away between

a dune and the railroad tracks. There I stomped on the emergency

brake.

By dinner's end, my mood had brightened. In the

distance to the northeast we identified the craggy spires of

King Lear Peak blazing orange in the setting sunlight. They

looked impossible far away, and we considered rethinking our

next destination. The wind picked up and began to blow cold.

West across the playa heavy black clouds gathered over the peaks

of the Calico Range. By sunset the wind howled, blowing over

our lawn chairs and everything else not tied down. The clouds

looked nasty. We turned in without soaking in the hot spring.

That night it rained a little. To my delight, every 90 minutes

the blaring horn, rumble, and roar of a passing freight woke

us.

Tuesday

morning we arose early to calm winds and cold sunlight slanting

across the desert. Fresh snow dusted the upper slopes of the

Calicos. Wrapped in a towel, I padded over to the hot spring

and eased down the slimy bank. Barbara caught my photo just

as a BNSF freight rumbled past, then joined me in the soothing

hot water. All was well with the world.

Tuesday

morning we arose early to calm winds and cold sunlight slanting

across the desert. Fresh snow dusted the upper slopes of the

Calicos. Wrapped in a towel, I padded over to the hot spring

and eased down the slimy bank. Barbara caught my photo just

as a BNSF freight rumbled past, then joined me in the soothing

hot water. All was well with the world.

After breakfast we repacked the van. One of the

campers was having trouble starting his diesel engine. They

had pushed the truck around and opened the hood so the sun would

warm the glow-plugs. We chatted for awhile. One of the men explained

how they had once camped at Little High Rock Canyon, and recommended

it. The canyon was beautiful. He described the entrance road

circling a reservoir and ending at a grassy meadow.

We had already decided not to follow the rocky

road on to King Lear Peak. For that we might return someday

in a rented four-wheel-drive. So we retraced our route to Bruno's

Casino and Cafe in Gerlach. As we ate lunch, we reviewed our

literature. The Sierra Club guidebook had a provocative description

of Little High Rock Canyon, and the west entrance appeared accessible

by passenger car from State Road 34. On the laptop I found the

coordinates of the turnoff and entered them into the GPS. After

lunch Barbara visited the Burning Man office and learned that

the festival was held at a BLM site on the playa accessed at

the nine-mile turnoff north of Gerlach on Highway 34. We decided

to check it out on our way.

Gingerly

we drove down the access ramp and out on the playa, parked,

and got out, scuttling like ragged claws across the floor of

extinct Lake Lahontan, its surface once 500 feet above our heads.

The ancient lake vanished shortly after the Pleistocene epoch,

leaving only Pyramid, Winnemucca, and Walker Lakes and the Carson

Sink as its remnants. The playa was huge and featureless, blindingly

white, and disorienting. Distant mountains reflected in the

mirage shimmering above the alkali surface as we strolled away

from the van, which soon appeared minuscule and insignificant.

A man could get lost out there, or stuck in the cloying white

mud that followed a rain storm. A man could die of thirst. We

found no sign of the Burning Man.

Gingerly

we drove down the access ramp and out on the playa, parked,

and got out, scuttling like ragged claws across the floor of

extinct Lake Lahontan, its surface once 500 feet above our heads.

The ancient lake vanished shortly after the Pleistocene epoch,

leaving only Pyramid, Winnemucca, and Walker Lakes and the Carson

Sink as its remnants. The playa was huge and featureless, blindingly

white, and disorienting. Distant mountains reflected in the

mirage shimmering above the alkali surface as we strolled away

from the van, which soon appeared minuscule and insignificant.

A man could get lost out there, or stuck in the cloying white

mud that followed a rain storm. A man could die of thirst. We

found no sign of the Burning Man.

As we left the playa and climbed toward the western

slopes of the Calicos, the pavement ended and the gravel road

climbed up the canyon carved by South Willow Creek. Though well

graded, the gravel gave way to steep, rocky dips where the creek

flowed across the road. There a vehicle might get mired and

swept away in a flash flood. The van fishtailed across two particularly

treacherous crossings.

Where the GPS told us it should

be, there was no turnoff to Little High Rock Canyon. No road

sign. But back to the east was a cleft in the mountain rim we

judged to be the canyon. A little further along, six-tenths

of a mile north of the Duck Flat Road (N41 13' 34.6", W119

29' 26.6"),  we

found a rough, unmarked dirt track descending into the sagebrush

toward the canyon. We crawled down the narrow, bumpy road, gunning

across a few muddy ruts, hoping we would not have to turn around.

We came to a fork, both roads appearing equally traveled. We

chose the one to the right, which curved toward the canyon.

(Later we learned the left fork led to Denio Camp.) Our track

circled above a dammed reservoir (just like the fellow at Trego

had said), a quarter full of water, then dropped to a muddy

stream crossing in the middle of a broad wet meadow. For 30

feet the road was a bog where the stream flowed through deep,

muddy ruts. We parked the van, a little over four road miles

from Road 34.

we

found a rough, unmarked dirt track descending into the sagebrush

toward the canyon. We crawled down the narrow, bumpy road, gunning

across a few muddy ruts, hoping we would not have to turn around.

We came to a fork, both roads appearing equally traveled. We

chose the one to the right, which curved toward the canyon.

(Later we learned the left fork led to Denio Camp.) Our track

circled above a dammed reservoir (just like the fellow at Trego

had said), a quarter full of water, then dropped to a muddy

stream crossing in the middle of a broad wet meadow. For 30

feet the road was a bog where the stream flowed through deep,

muddy ruts. We parked the van, a little over four road miles

from Road 34.

We looked the place over. An amazing abundance

of cow pies adorned the green sward, and cattle watched us from

the surrounding tall sage. Bits of black obsidian peppered the

rocky, alkali dirt. Here at the stream crossing, we agreed,

would be a fine spot to camp. We locked the van to explore further

down the road.

On the far side of the muddy

crossing the road climbed a hill, then forked. The right-hand

fork wound down toward the cleft in the mountain, which, as

we approached, began to look like a chocolate-lemon layer cake

that had been sliced open and a single piece removed. Sage frosted

the slopes like mint icing. This had to be the mouth of High

Rock Canyon. We followed the road for a half-mile until we came

to a gate at the canyon's narrow entrance.  A

barbed-wire fence stretched high enough up into the rim rock

on each side to keep the cows out. The wire gate, of course,

lay wide open in neglect or defiance. This was Nevada. No signs

were posted, but we surmised that we stood on the threshold

of the wilderness (N41 15' 23.3", W119 25' 02.7").

A

barbed-wire fence stretched high enough up into the rim rock

on each side to keep the cows out. The wire gate, of course,

lay wide open in neglect or defiance. This was Nevada. No signs

were posted, but we surmised that we stood on the threshold

of the wilderness (N41 15' 23.3", W119 25' 02.7").

Tentatively we took a few steps into the canyon's

mouth. The walls were stunningly high rock cliffs, the bottom

beautifully green and inviting. A definite trail followed the

creek along the canyon floor, but we could not see past the

first bend, so we could not tell how far. We lingered a while

before returning to the van, closing the gate as we departed.

On the way back, at a ten-foot high strata of

white alkali deposits exposed in the cliff above the road, we

saw a short line of white tines sticking up like an overturned

xylophone. We climbed up to investigate. There, before a shallow

cave, lay the skeleton of a complete dead cow, ribs sticking

into the air and a bit of hide still clinging to the hoofs and

snout. We wondered if it had died naturally in that unlikely

place, or if someone (or some thing) had dragged it there

to eat, or as a warning to wolves, or rustlers, or to keep the

herd in line, or for some mysterious dark ceremonial purpose

only the Nevadan mind could grasp.

That evening, as we ate dinner, cows began to

crowd around us. I threw a few lame rocks, but they refused

to disperse. They faced our van in a picket line like disgruntled

Teamsters striking for a new contract. With maddening bovine

inscrutability they watched us eat. What did they want from

us? Were we blocking their path? Or did they want us to feed

them? We did our best to ignore them, and after a while they

slowly melted back to their forage.

It rained a little on Wednesday morning, turning

the soil and cow manure into a muddy paste that cemented in

the waffle soles of our hiking boots. Then a bright sun played

peek-a-boo with the lingering low clouds. As we lounged at the

campsite, we saw a grey flycatcher, robins, a shrike, and killdeer.

A melodious bird sang from hiding in the sage. Mid-morning coyotes

wailed nearby, reminding us of the ceremonial cow skeleton down

the road. We decided to spend the day reconnoitering in the

canyon to see if the trail ran all the way down and whether

there would be any place to camp.

Before noon we started into the canyon with daypacks,

immediately crossing the shallow creek on wet rocks. The canyon

curved sharply right, then slalommed back and forth beneath

ever rising rimrock painted yellow with lichen. As we hiked,

the canyon opened. The trail cut through tall sagebrush, eight-feet

high in places, and crossed and recrossed the creek as it meandered

from wall to wall. Growing in and along the stream were willow,

western serviceberry, rye and bunch grass, wild rose and current,

chokeberry, and, as we each painfully discovered, nettles. Larkspur,

penstamon, phlox, yellow Mariposa buttercup, and other flowers

we did not know brightened the slopes and meadows. Ahead swallows

and magpies flew among the cliffs, and a red-tailed hawk soared

high above. Barbara heard the descending trill of a canyon wren.

We found no sign of campsites or fire rings in

the brush. But there was a massive quantity of horse and cow

manure along the well-used corridor, which was probably a thoroughfare

for working buckaroos. In places the creek grew still, deep,

and muddy with alkali runoff turning the water milky. We wondered

if our water filter would clog if we tried to camp in the canyon.

Above us in the rimrock on the north slope several caves offered

spooky shelter. The entrance of the largest one was barred by

an elaborate grid of rusting welded-iron strap, the only sign

of human presence in the canyon.

After a while the floor of the canyon broadened

into a 300-feet wide pastureland. Sagebrush grew short and sparse,

replaced by lush green rye and bunch grass. We encountered no

grazing cattle. Overhead a peregrine falcon flew from wall to

wall, keeping a wary watch on us. When we stopped for lunch,

the bird flew to its nest at the mouth of a hanging side canyon.

A group of large raucous birds, gray with boldly barred flanks,

scolded us from the rimrock. We later keyed them out to be chukar.

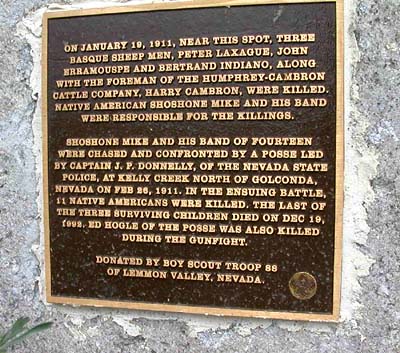

"What's that?" Barbara asked, pointing

out a square plaque at the base of the towering cliff across

the creek to the south. It appeared to be a grave marker, or

a memorial to someone coldcocked by a falling slab of rock.

Even through the binoculars, Barbara could not quite make out

the words. So I hopped and squished across the creek to approach

the plaque. It read:

I found the Boy Scout marker annoying. The

whole thing felt wrong. Discordant. From its rectangular

carcass reeked the aroma of rotting fish and indoctrination. Like

the stench that must have filled the halls when Hitler Youth were

taught Aryan Supremacy. Or Andrew Jackson preached Manifest Destiny

to land-hungry pioneers. Those bright-eyed little Boy Scouts,

all wrapped in their flags and honor, had been fed the party line

by some crew-cut scoutmaster not born when the incident took place.

I wanted to hear the Indians' side of the story. Not until we

returned home, however, was I able to dig out the complete story

of the sad and sordid affair known as the "Last

Indian Battle".

We hiked out beneath threatening clouds and intermittent drizzle,

arriving back at the van around 4 P.M. The wind had picked up.

As we pondered what to do, a bright yellow-and-black bird serenaded

us from a stalk of sage. It was the Meadowlark we had heard,

but not identified, that morning. After dinner we followed a

spur road as it wound up the hillside above our camp. In the

distance to the east we saw a mineshaft or shelter of some sort

not far from the van. We crossed the creek and followed the

road up the east fork until we came to an old homestead, with

a collapsing shack built into the side of hill. The map identified

the place as Woodruff Camp. It appeared long abandoned by sheep

herders and buckaroos.

That evening we heard the coyotes again. In the

night, something thumping and scraping beside the van, awakening

Barbara. She told herself it was only cattle and fell back asleep.

Thursday morning the sky was clear and the sun

warm, although thunderclouds still ringed the horizon. As we

contemplated the ambiguous weather, Barbara identified a sage

thrasher and brown-headed cowbird. I wanted to try backpacking

into the canyon for at least one night. It had been ten months

since our last backpack. Our last weather report, though a week

old, had talked of a warming trend in the latter part of the

week. Barbara expressed concern about getting caught in a flash

flood in the canyon, but reluctantly agreed. But by the time

we had loaded and strapped on our packs, the noose of dark clouds

had tightened. Maybe it would pass over.

Once again we hiked down the road, past the ceremonial

cow skeleton, and through the gate into Little High Rock Canyon.

The familiar trail made for easy hiking. By noon we had reached

the broad pasture that I now thought of as Shoshone Mike's stronghold.

The sky had completely clouded over.  Before

we could find a place to set down our packs, the drizzle began.

We whipped out our ponchos and helped each other don them over

our packs. The drizzle turned into a steady rain. I spotted

a fractured indentation in the cliff wall not far from the Shoshone

Mike plaque, where the overhanging rock might keep us dry. In

a steady rain we crossed the creek and unloaded our backpacks

under the cliff. There we sat squeezed into the dry hollow and

ate lunch. Soon it dawned on us that the jagged, sharp slabs

of rock that made up the ceiling of our niche were loose and

could fall on us from the overhang. We needed overhead airbags.

Before

we could find a place to set down our packs, the drizzle began.

We whipped out our ponchos and helped each other don them over

our packs. The drizzle turned into a steady rain. I spotted

a fractured indentation in the cliff wall not far from the Shoshone

Mike plaque, where the overhanging rock might keep us dry. In

a steady rain we crossed the creek and unloaded our backpacks

under the cliff. There we sat squeezed into the dry hollow and

ate lunch. Soon it dawned on us that the jagged, sharp slabs

of rock that made up the ceiling of our niche were loose and

could fall on us from the overhang. We needed overhead airbags.

After lunch the rain tapered

off, then stopped. We bided our time as showers came and went,

trying to decide whether to stay or go. I built a campfire ring

near the cliff and pumped water from the creek. The skies cleared

overhead, but deep in the canyon we had no view of the horizon

and what might be coming. Maybe the rain was done. In a glow

of optimism, we set up the tent beneath blue sky (N41 15' 19.4",

W119 23' 34.5"). (See Opening Photo).

I tossed a line over a rock projecting from the cliff face and

hung the food bags, although bears were unlikely in that treeless

land. Then we cut firewood from a thick stump of sage with the

new pocket chainsaw. We ate an early supper, just in case.

Barbara worried that in a mountain deluge the

creek might rise. A flash flood might wash us away. I treated

the possibility as remote, pointing out that the creek would

have to rise five feet to threaten our tent. Besides, the weather

forecast predicted that skies were bound to clear.

After dinner the sky grew ominously dark. Approaching

thunder and lightning crackled on the cliffs. Barbara dashed

into the tent as the first fat drops began to splatter. I found

shelter standing in the cleft beneath the rock face. The rain

fell in gusty sheets. The tent shook in the wind like a wet

puppy trying to whip loose its tether.

I heard a droning howl I thought at first was

an owl, but the sound began to rise and fall like an old Indian

chant. "What the hell." My eyes explored the

cliffs and canyons for a lurking band of renegades. Nothing.

Straining to hear through the rain and wind, I thought the sound

was coming from the tent.

"Are you saying something," I

yelled into the gale.

"Can't . . . hear you," Barbara

yelled back. "Turn on . . . radio."

I found the radio in my pack and turned it on.

"Are you saying something?"

"Oh . . . ." There was a pause. "I

was just beseeching the clouds to go away." Another pause.

"I didn't know you could hear me."

I howled. Barbara howled. The wind continued to

howl. Soon the howling ended and the rain let up. Barbara crawled

out of the tent into a newly washed world. A few rays of dazzling

sunlight glanced from the west, warming, but too feeble to dry.

The storm had passed, and the humid air grew calm. Our wet tent

drooped, but the inside remained dry. I reinforced the corner

stakes with slabs of rock and tightened the lines. We crept

in early and, warm in our down bags and soothed by the patter

of intermittent showers on the taut rainfly, slept well.

Friday

morning was magical. The canyon lay lush green and soaking in

the bright sun. Fat droplets clung to every stem and stalk,

reflecting each other like the jewels of Indra's web. We emerged

from our chrysalises and unfurled our wings to dry in a sunny

patch of grassland between the rock wall and the stream. Unhurried,

seated on our mats, we sipped our tea and mocha, listened to

a chorus of mourning doves and chukar, and traced the flight

of a flicker and peregrine falcon across the clear blue sky.

Ah, this! Nowhere better to be. Nothing better to do.

The world seemed right. In serene peace we ate our oatmeal and

dried fruit.

Friday

morning was magical. The canyon lay lush green and soaking in

the bright sun. Fat droplets clung to every stem and stalk,

reflecting each other like the jewels of Indra's web. We emerged

from our chrysalises and unfurled our wings to dry in a sunny

patch of grassland between the rock wall and the stream. Unhurried,

seated on our mats, we sipped our tea and mocha, listened to

a chorus of mourning doves and chukar, and traced the flight

of a flicker and peregrine falcon across the clear blue sky.

Ah, this! Nowhere better to be. Nothing better to do.

The world seemed right. In serene peace we ate our oatmeal and

dried fruit.

By midmorning the sun had dried our tent, but

storm clouds grew in the "V" of canyon to the west.

We decided to pack up and hike out. By noon, as we crossed the

creek near the canyon mouth, the drizzle began. A steady rain

fell as we climbed the road to the van. The rain soon ceased,

but patches of blue sky were being crowded out by waves of swelling

cumulus. It was time to move on.

A serious storm blackened clouds and closed in

around us as we fled south on Road 34 toward Gerlach, hoping

to cross the washes before they churned with flood waters. A

few miles before the last and deepest stream crossing, the deluge

hit. Rain poured down on the sage-covered hills and sheeted

off slickrock canyons. We managed to careen across the liquefied

gravel of the final stream bed before the water become impassible.

At Gerlach we stopped for lunch, then drove south

on the two-lane blacktop of Highway 447 into the eye of another

storm. Rain pelted the van until we passed through. The road

followed the eastern flank of the Fox Range to Winnemucca Lake,

another mostly dry playa remnant of Lake Lahontan cradled between

the Lake Range and the Nightingale Mountains. The high desert

was in bloom and a hatch of butterflies spattered our windshield.

The highway entered the Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation,

with its impoverished little towns and isolated, lonesome houses,

yards cluttered with junk and abandoned autos. Were these Paiutes

or Shoshone? We had no way of knowing, but sensed smouldering

resentment. The federal government's promise of Indian gaming

was no economic deliverance for Nevada tribes, where legal gambling

had long saturated the culture. Before long we passed Pyramid

Lake, whose lovely, wild, wind-waved surface stretched far to

the northwest. These sparkling waters formed the final sink

for the abundant flow of the Truckee River. White men had neglected

to steal this beautiful lake from the Native Americans. We wondered

why.

Finally leaving the reservation, the road crossed

the Truckee River at Wadsworth, and we felt ourselves spilling

down a rabbit hole into another world. Everything was in restless

motion. The I-80 corridor dazzled us with sodium lights, speeding

traffic, neon advertisements, and casinos. We had reentered

the realm of brash Nevadan hustle, where Boy Scout begat Boy

Scout and the sole moral principle was profit. Forgotten was

the drumbeat of the desert, the rhythm of the range, the voice

of the vanquished.

Entering Fernley was like descending into the

first circle of hell. The only vacancy we could find was at

a place called the TruckInn, a surreal combination of truck

stop, casino, motel, restaurant, and bar. A full-sized 18-wheeler

had been erected on a fifty-foot pole outside as a bizarre icon

of all the place had to offer. As we checked in, the clerk demanded

a deposit to obtain a television remote, which spoke darkly

of the usual clientele. In the hallways prowled unruly young

men with baseball caps and bulging tattoos, while wild girls

sauntered with exposed midriffs. We could not be certain that

bandits and psycho-killers lurked in the dimly lit corridors,

but we locked ourselves in our room until the morning sun drove

them all back underground.

Saturday morning we drove west on Interstate 80,

following the Truckee upriver. Everywhere the mountains had

been clawed open and their chalky insides mined. The naked hills

were defaced with roads, antennas, and ORV tracks. We glided

past the infamous Mustang Ranch. At Sparks we entered the brown

air of the Reno Valley. Bred in moist swamps along the river,

the Nevadan culture had proliferated like a slime mold and climbed

the valley walls. The freeway carved a path through the built

out, paved over, and wanton sprawl. We escaped north on Highway

395 into California.

Return to Backpacking

in Jefferson